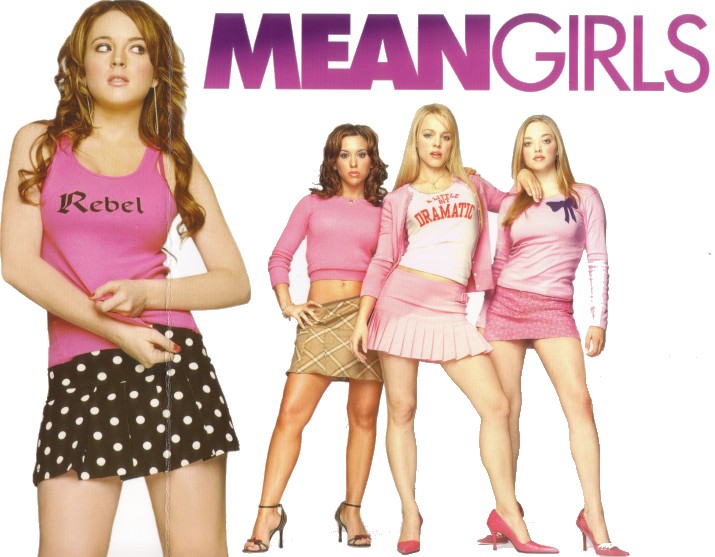

At first glance, Mean Girls, is a shallow film about high school girls and their drama. However, with a closer watching, armed with some knowledge, the viewer can see an entirely new storyline emerge. Regina George, a pretty and popular blonde, constantly has to portray her peers’ idea of the “perfection” that she is. Regina George is, in fact, completely controlled by her own need to act as, or perform, the so-called “perfect” woman. The 2004 film, Mean Girls, is an example of how strict gender performances police same sex desire and reinforce heteronormativity.

At first glance, Mean Girls, is a shallow film about high school girls and their drama. However, with a closer watching, armed with some knowledge, the viewer can see an entirely new storyline emerge. Regina George, a pretty and popular blonde, constantly has to portray her peers’ idea of the “perfection” that she is. Regina George is, in fact, completely controlled by her own need to act as, or perform, the so-called “perfect” woman. The 2004 film, Mean Girls, is an example of how strict gender performances police same sex desire and reinforce heteronormativity. Regina George is what the entire student body would call “perfection”. In the clip below, it can be seen just how many students look up to Regina. In the last few seconds of the clip, an unattractive female student says, “One time, she [Regina] punched me in the face. It was awesome” (Mean Girls). Regina George is what most of the student body looks to as the ideal woman—men love her and woman want to be her.

Regina George is what the entire student body would call “perfection”. In the clip below, it can be seen just how many students look up to Regina. In the last few seconds of the clip, an unattractive female student says, “One time, she [Regina] punched me in the face. It was awesome” (Mean Girls). Regina George is what most of the student body looks to as the ideal woman—men love her and woman want to be her.With this ideal woman, however, comes great responsibility. Regina George is not naturally this wonderful. That is, “the building blocks of gender are socially constructed statuses,” (Lorber 55)—not naturally bestowed traits. By this assumption, Regina George is constantly being forced to “perform” her gender in order for other people to admire her. Her main goal is to attract the necessary male counterpart; however, her seeming perfection catches the eyes of more than just men. Regina performs the societal heteronormative to perfection. Yes, Regina was born with society’s idea of beauty. She was once again blessed when she was born into an affluent family. However, she was not born a “woman” by the standards of modern American society (as depicted in this film).

If Regina George was not born woman, then what is she? The evidence in the film seems to suggest that she is over compensating for her natural lesbian tendencies. As the most beautiful woman on campus, she is expected to date the most handsome man on campus. Theorist Adrienne Rich believes that man’s power over a woman dictates her sexuality—and only the women strong enough to escape the expectations are truly free. Rich defines a lesbian experience as a “woman-identified experience, not simply the fact that a woman has had or consciously desired genital sexual experience with another woman” (305). With this definition, the relationship of Regina and her fellow “Plastics,” or best friends, becomes much more clear. Regina George, while constantly bombarded by the societal norms, feels the need to identify with peers of her own gender. While her character never seems to show any lesbian tendencies toward her peers, she does nothing to reject those advances. The most queer relationships in the film are between the Plastics. These select girls follow Regina, their queen bee, religiously. The Plastics are neither as pretty nor as popular as Regina, but are still fit to be seen near her. Regina treats them as second-class citizens (and the rest of the school is unfit for any treatment). It is with the Plastics, but Gretchen Weiners in particular, that the most complicated and fascinating relationships in the movie become much more clear.

Gretchen Weiners, Regina’s best friend, is the exemplary form of queer. Judith Butler states that, “the professionalization of gayness requires a certain performance and production of a ‘self’ which is the constituted effect of a discourse that claims to ‘represent’ that self as a prior truth” (358). If this same theory applies being “professionally” straight, gender is constantly a performance. In Gretchen Weiners’ case, however, the performance is very lost. Gretchen, while wanting to remain the second most beautiful and popular girl in school, must act, as Regina George wants her to. The more that Gretchen acts, strangely, the easier it is to see her true intentions. Gretchen Weiners, while trying her hardest to confine to societal norms, is a lesbian. More specifically, Gretchen is in love with Regina George. Gretchen must suppress these feelings throughout the film, which, in turn, oppresses her natural desires. “Consciousness of oppression is not only a reaction to (fight against) oppression. It is also the whole conceptual reevaluation of the social world, its whole reorganization with new concepts, from the point of view of oppression” (Wittig 18). Gretchen becomes aware of her feelings for Regina about mid-way through the film, when she realizes that Cady Heron has taken her throne as second-in-command. Gretchen’s mental breakdown and realization occur in the following clip:

Gretchen Weiners, Regina’s best friend, is the exemplary form of queer. Judith Butler states that, “the professionalization of gayness requires a certain performance and production of a ‘self’ which is the constituted effect of a discourse that claims to ‘represent’ that self as a prior truth” (358). If this same theory applies being “professionally” straight, gender is constantly a performance. In Gretchen Weiners’ case, however, the performance is very lost. Gretchen, while wanting to remain the second most beautiful and popular girl in school, must act, as Regina George wants her to. The more that Gretchen acts, strangely, the easier it is to see her true intentions. Gretchen Weiners, while trying her hardest to confine to societal norms, is a lesbian. More specifically, Gretchen is in love with Regina George. Gretchen must suppress these feelings throughout the film, which, in turn, oppresses her natural desires. “Consciousness of oppression is not only a reaction to (fight against) oppression. It is also the whole conceptual reevaluation of the social world, its whole reorganization with new concepts, from the point of view of oppression” (Wittig 18). Gretchen becomes aware of her feelings for Regina about mid-way through the film, when she realizes that Cady Heron has taken her throne as second-in-command. Gretchen’s mental breakdown and realization occur in the following clip:Gretchen Weiners further proves her lesbianism by her accusation of Janice Ian. In the “burn book,” a book in which the Plastics write insults about inferior classmates, Gretchen wrote “Janice Ian—Dyke!” (Mean Girls). People who feel they are alone will constantly try to identify with others who they feel may be in the same situation. Gretchen decided to choose an unpopular girl and accuse her of being a lesbian, in order to make herself feel more comfortable with her sexuality.

Gretchen is overcompensating by trying to display what she believes is heteronormative, or normal behavior for heterosexuals. Her action has several motives, but the most apparent being the need to identify with another. Another possible motive is that Gretchen Weiners has spent too much energy trying to perform in the manner that she feels is normative and she needs a way to release her true desires. This could be a desire toward Janice Ian, or just an indirect way of gaining Regina’s acceptance.

This idea brings film into its main point (from a queer theory analyst’s point of view). Gretchen Weiners, while beautiful, rich, and popular, does not feel comfortable with who she is as a woman or sexually. Constantly trying to perform her gender role in a modern American society has not only been difficult, but also taxing. Gretchen hits a point in the film when she can no longer perform; from that point on, Gretchen’s lesbianism is much more apparent. From her jealousy of Cady, to her accusations toward fellow students, Gretchen proves that conforming to a strict gender performance attributes to a same-sex desire—not a heteronormative lifestyle.

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. “Imitation and Gender Insubordination”. The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. Ed. Henry, Aina, and Halperin. New York: Routledge, 1993. Pp. 354-71. Print.

Lorber, Judith. “’Night to his Day’: Social Construction of Gender”. The Inequality Reader: Contemporary and Foundational Readings in Race, Class, and Gender. Ed. Grusky and Szelényi. Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 2007. Pp. 53-68. Print.

Mean Girls. Perf. Lindsey Lohan, Rachel McAdams, and Tina Fey. Paramount Pictures, 2004. DVD.

Rich, Adrienne. “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence”. The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. Ed. Henry, Aina, and Halperin. New York: Routledge, 1993. Pp. 304-12. Print.

Wittig, Monique. “One is not Born a Woman”. The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader. Ed. Henry, Aina, and Halperin. New York: Routledge, 1993. Pp. 9-20. Print

0 comments:

Post a Comment